Understanding Food Tolerance

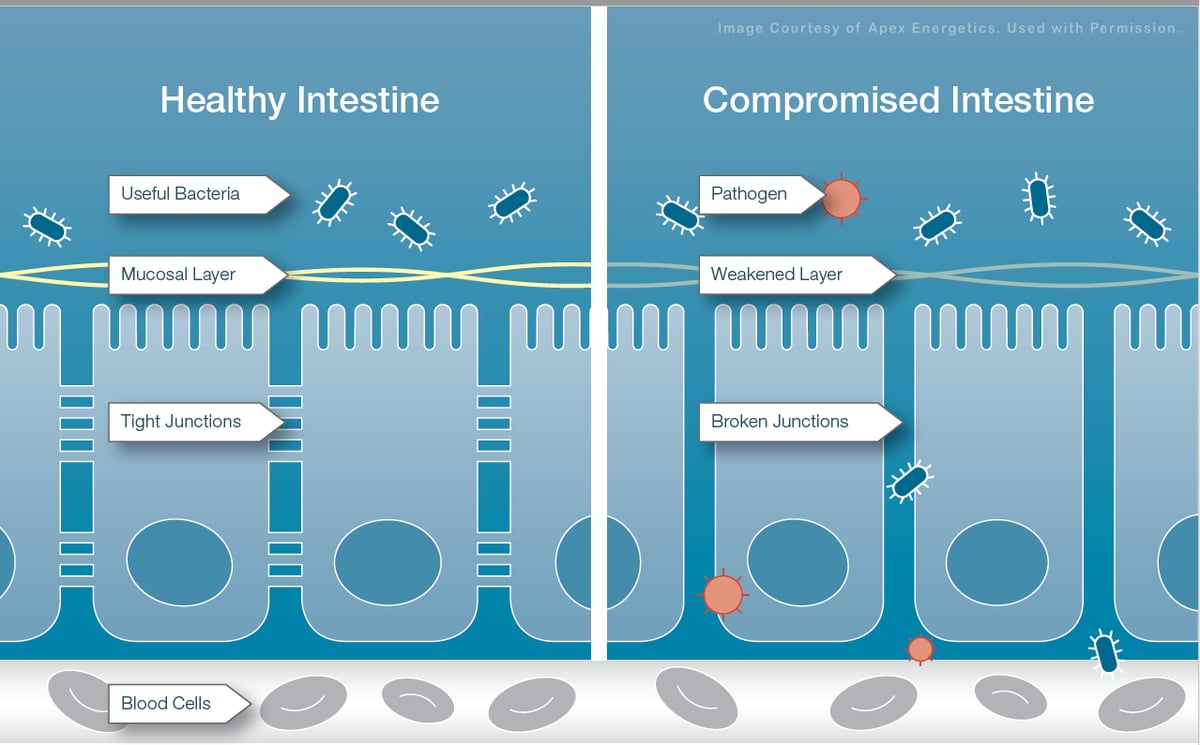

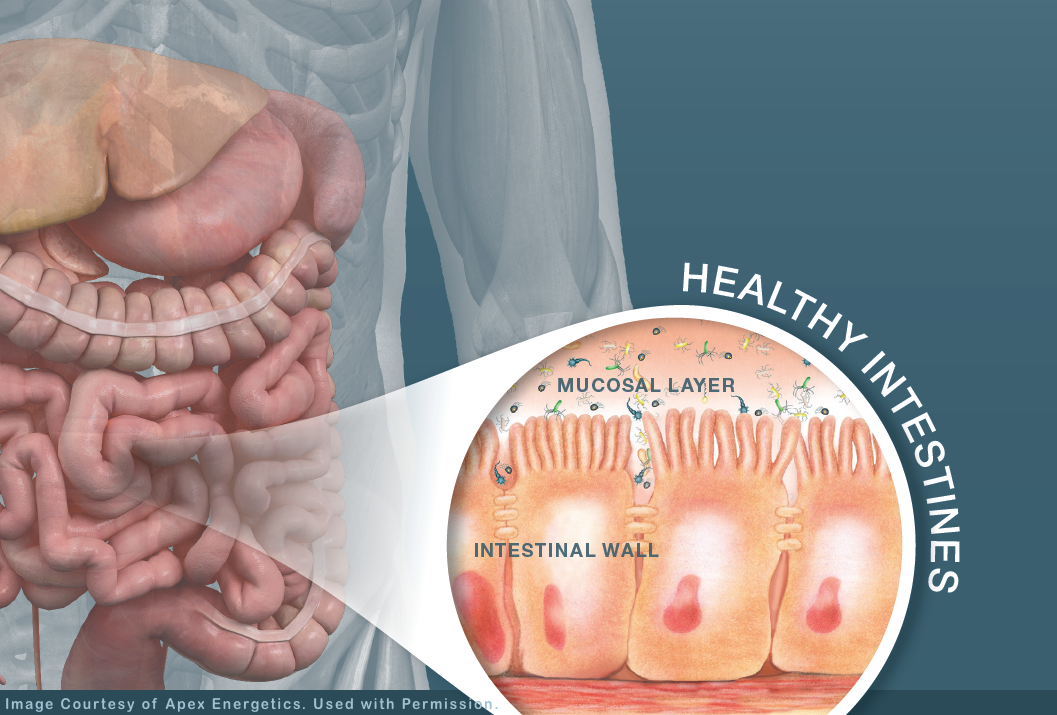

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the region of our body that directly interacts with the external world through the foods we eat. Our GI tract performs two main functions. First, it allows us to absorb nutrients critical to maintaining our health. Second, its protective immune system shields us from pathogens, such as bacteria and foreign invaders. The area of our GI tract—from the esophagus to the rectum—where we absorb nutrients and have our protective immune system consists of a specialized line of cells, called the “mucosal layer.”

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the region of our body that directly interacts with the external world through the foods we eat. Our GI tract performs two main functions. First, it allows us to absorb nutrients critical to maintaining our health. Second, its protective immune system shields us from pathogens, such as bacteria and foreign invaders. The area of our GI tract—from the esophagus to the rectum—where we absorb nutrients and have our protective immune system consists of a specialized line of cells, called the “mucosal layer.”

Identifying and Removing Reactive Foods

Identifying and removing reactive foods can be a good first-step strategy that may impact energy levels, skin appearance, digestive comfort, well-being, mood, and more. When multiple food reactions are identified, your healthcare professional may recommend removing those foods from the diet. Taking steps to support the GI mucosa and immune system and address any environmental concerns, as recommended by your healthcare professional, may also be beneficial.

The Mucosal Layer

The mucosal layer is the first protective barrier in the intestines which, when compromised, can lead to immune intolerance, food sensitivities, and food reactions. The mucosa constantly evaluates all foreign proteins that are ingested, including food proteins, and distinguishes which proteins are self or foreign material. This function involves the local immune system throughout the GI tract and plays a major role in forming what is called “immune tolerance” or “oral tolerance.” [1]

The Cellular Barrier

The cells in the intestines under the mucosal protective layer are equipped with tight junctions, enabling them to bridge between the cells and form a tight barrier that only allows extremely small molecules to pass through. However, tight junctions can selectively open their gates to allow certain antigens through; this function is coordinated with the immune system.

The GI Immune System

The physiological function of the local GI immune system, known as “gut-associated lymphoid tissue” (GALT), does not usually result in immune reactions against selfproteins, but protects against pathogens. The tolerance of mucosal immunity depends upon intentionally dampening the immune reaction against friendly antigens, such as those found in common foods. If this dampening does not occur, immune reactions to foods may develop. This food-immune reactivity is not an allergy or disease at this point, but it may cause diverse, nonspecific discomfort throughout the body.

Proper Digestion Critical for Immune Tolerance

Mucosal immune tolerance starts with the proper breakdown of foods by digestive enzymes. Our body produces various digestive enzymes that help break down proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. The most active digestive factors in the stomach include hydrochloric acid and pepsin.

However, the most comprehensive and effective groups of digestive enzymes are found in the small intestine and include protease, amylase, lipase, sucrase, phytase, pectinase, cellulase, lactase, alphagalactosidase, and glycoamylase. All of these enzymes together provide and support a complete digestive process. These enzymes break down the foods we eat into amino acids, sugars, and other small particles that are then absorbed by our mucosa.

If food proteins are not broken down into smaller peptides, the mucosa may not recognize these compounds and may react to them as if they are foreign compounds.

Tight Junctions - How The Intestines Protect US

Once the foods we eat are properly broken down, they are absorbed in the small intestine. Normally, food proteins—even if broken down into small peptides—cannot penetrate the tight junctions.

However, intestinal tight junctions may be affected by factors, such as poor diet, and environmental stress factors and triggers, such as gluten sensitivity and microbial invasion, which may play a role in the loss of tolerance to dietary proteins. Some immune triggering peptides may breach the intestinal tight junctions and promote further impact on these tight junctions, creating a vicious cycle. When the intestinal tight juctions are breached, we call this "leaky gut" and often a breach of the blood-brain barrier ("leaky brain") can be triggered from long-standing "leaky gut". Researchers have found many neurobehavioral disorders are linked to leaky brain. [2]

In our office, we assist our patients with a comprehensive approach to ADD/ADHD, Asperger's Syndrome, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbane, mTBI that includes helping repair leaky gut and leaky brain and neurofeedback.

Nutritional Strategies May Help The GI Tract Stay Healthy

Ingested dietary food proteins travel down the GI tract from the small intestine to the large intestine. A special group of immune cells in the gut wall called “dendritic cells” sample and introduce the antigenic sections of each protein to the immune system, determining if immune reactivity is necessary.

Key vitamin support, including both vitamin A [3] and vitamin D [4], has been implicated in these immune processes and thus has potential to support food immune tolerance.* Additionally, a healthy and diverse intestinal bacterial environment appears to play a critical role in mucosal immune tolerance. [5-6]

Various strains of beneficial probiotics and dietary short-chain fatty acids, or SCFAs (eg, butyrate, propionate, and acetate), which promote healthy microbial environment development, also appear to have a positive role in mucosal health and tolerance. [7-10]*

The mucosa selects and transports protein antigens to lymph nodes throughout the intestines. In lymph nodes, they are sampled by immune cells to determine if the dietary protein is a “friend” or “foe.” The key immune cell necessary for immune tolerance is called a “regulatory T-cell” (T-reg cell), which is supported by vitamin D [11] and glutathione. [12]* After food proteins are broken down and absorbed, they are transported from intestinal circulation to the liver, where they are sampled and reacted upon by immune cells in the liver called Kupffer cells. Toxic compounds, environmental antigens, and hepatic clearance capacity are among the factors that can influence immune reactivity in the liver. Adequate levels of the antioxidant glutathione and healthy liver clearance may also contribute to mucosal health and tolerance.

Dietary interventions may play an integral role in properly supporting mucosal health. Dietary recommendations should be determined by your healthcare professional, as food sensitivities need to be considered based on clinical evaluation.

The copyrighted material for this article and the images are sourced from educational material provided by Apex Energetics and are used by permission. www.apexenergetics.com

Always remember one of my mantras., "The more you know about how your body works, the better you can take care of yourself."

For more details about the natural approach I take with my patients, take a look at the book I wrote entitled: Reclaim Your Life; Your Guide To Revealing Your Body's Life-Changing Secrets For Renewed Health. It is available in my office or at Amazon and many other book outlets. If you found value in this article, please use the social sharing icons at the top of this post and please share with those you know who are still suffering with chronic health challenges, despite receiving medical management. Help me reach more people so they may regain their zest for living!

ALL THE BEST – DR. KARL R.O.S. JOHNSON, DC – DIGGING DEEPER TO FIND SOLUTIONS

References:

- Pabst O, Mowat AM. Oral tolerance to food protein. Mucosal Immunol. 2012 May;5(3):232-239.

- Obrenovich, M.E.M. Leaky Gut, Leaky Brain? Microorganisms 2018, 6, 107.

- Yang Y, Yuan Y, Tao Y, Wang W. Effects of vitamin A deficiency on mucosal immunity and response to intestinal infection in rats. Nutrition. 2011 Feb;27(2):227-232.

- Sun J. Vitamin D and mucosal immune function. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010 Nov;26(6):591-595.

- Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Moreau MC. Gut flora allows recovery of oral tolerance to ovalbumin in mice after transient breakdown mediated by cholera toxin or Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Pediatr Res. 1996 Apr;394(4 pt 1):625-629.

- O’Flaherty S, Saulnier DM, Pot B, Versalovic J. How can probiotics and prebiotics impact mucosal immunity? Gut Microbes. 2010 Sep;1(5):293-300.

- Murakoshi S, Fukatsu K, Omata J, et al. Effects of adding butyric acid to PN on gut-associated lymphoid tissue and mucosal immunoglobulin A levels. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011 Jul;35(4):465-472.

- Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, et al. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015 Jan;8(1):80-93.

- Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn AN, Mackay CR, Macia L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol. 2014;121:91-119.

- Talley NA, Chen F, King D, Jones M, Talley TJ. Short-chain fatty acids in the treatment of radiation proctitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997 Sep;40(9):1046-1050.

- Chambers ES, Hawrylowics CM. The impact of vitamin D on regulatory T cells. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011 Feb;11(1):29-36.

- Yan Z, Garg SK, Banerjee R. Regulatory T cells interfere with glutathione metabolism in dendritic cells and T cells. J Biol Chem. 2010 Dec 31;285(53):41525-41532.

* This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.